An Ode to the Caucasus: a Travel Diary

A saudadic girl* philosophising on language and times gone by (with photography).

ამიფინუ ხოლო (იგრიკა) დუმან / გიტრაღუდარ მოიბგარ ე ამან

اميپينو خولو (يگريکا) دومان / گيتراغودار مويبگار ي امان

amipinu xolo (İgriǩa) duman / giťrağudar moibgar e aman

the fog of (April) is coming again / don’t cry (I will sing a lament)

Chapter 1: the hecatomb that is time

I have always chased the feeling of times gone by.

Once, I would have called it “nostalgia”, but even then (Once), that word never felt like enough to encapsulate the sombreness of what I carried inside myself. It felt untranslatable. I now know that experience as something more akin to “saudade”.1 Or “hireth”.2 A melancholy yearning for something or someplace long lost.

“The love that remains.”

I grew up in the rural hinterlands, and every so often, we (my maternal grandmother and I) would catch an overnight train from the nearest “city” (population: ~16,000) to the country’s capital. We’d sit in the four-person coupé, sometimes across the fold-out table from strangers, and shuck shells off pistachios as that old locomotive cut through thick forest and passed dozens of villages tucked under fir needles and toadstools. Tuh-tun, tuh-tun. Tuh-tun, tuh-tun. The train would go with few as one or two connecting stops all the way to the first city. Some trips, lush green canopies of oaks and birches embowered the sinking tracks. Others, an untouched, crystalline whiteness swaddled the landscape and pines stretched their shúba-cloaked arms for the train running by. It was such an impossibly flat land. One night, I awoke with the train resting at one of those connecting stops (much to my endless chagrin and whingeing, my grandmother never really let me sleep on the top bunk when I was little for fear of me falling off). The deepnight had this tint of blue like van Gogh’s paintings and a thick sheet of ice coated the station, glistening under the full-bellied moon. The train slept and not a soul dwelt outside—I couldn’t even see any rooftops afield. The cosmos stood so still, so silent; a liminal space; a waking dream. I must have been four or five. It’s one of my most vivid childhood memories.

We’d always leave that “city” (population: ~16,000) early in the morning, and step out into the capital even earlier the next. If I woke up just right, I could watch the train chug through the industrial plexus of hundreds of railroads and pull into the grand city (real city!) station. I’d almost cry when getting off the train because I was so scared of falling through the gap, and then my grandmother would pull me by the hand through the murmuration of passengers and out of the station’s valves. The air was crisp no matter the season with such early hour’s septentrional sun barely skating the pavement, and people murmured beneath echoes of digitised announcements of departures and arrivals like pigeons cooing under eaves. My four-year-old self thought the whole world must live there! In that station.

I think those scenes are why I still love the dawn so much, even though I feel awful waking up that early. I have always chased the feeling of times gone by.

That train doesn’t run anymore.

Too few people must live in that “city” now for the government to think it worth its time to send the thing. I’ve cried an embarrassing amount over the reality that I’ll never be able to relive those exact childhood trips again, even if they were to a city I despite (and yet I still miss it, in some pathological way). There is a drawing I once made in hopes of capturing my saudade for that train route. For those stations. That time.

I haven’t drawn in many months. Ruby Ḥamad said something on an adjacent subject in March. “What use is writing in a time like this?” Isn’t it ironic that here I am?

Time is a hecatomb.

My girlhood* was between the concrete walls of the khrushchyóvka and the untouched boreal woods. And maybe I’m a bad person for missing home. And maybe I’m a worse person for thinking of it like that at all.

But there was a place, a feeling, a time gone by, that I chase more fervidly than any other.

It was yet another overnight train away, where that impossible flatness soared into the tallest peak of upper West Asia:3 Circassia’s Waschḥɛmakhwɛ.4 “Bless’ed mountain”. What the Russians call “Elbrus” (Эльбрус). From Avestan Harā Bərəzaitī, a mythical Zoroastrian peak and also the root of the Alborz (البرز) mountain range in Irân.

The trip was so long, time blurred, and I’m sure there’s an irony there too, but I remember gilded afternoon rays of summer stretching across the floor of the train wagon and mountains burgeoning on the horizon. The train was platzkart, this time, not coupé, so I’d wander up and down the aisle, and sometimes I’d pause to talk to random people drinking tea, even though I was such a shy kid. And sometimes an elderly grandpa would hand me a chocolate wrapped in shiny, crinkly, aluminium. There was a lady my mother’s age there, too, with hot pink nails. At one point, I saw her hand hanging off the top bunk and thought she was my mother because she also had some sort of off-pink-off-lilac nails. I find it fascinating what I recall so clearly, and what barely comes to mind.

I know my mother’s and her mother’s eyes were on me like a pair of hawks, but I nonetheless felt so adventurous traversing the carriage. I still wasn’t allowed to sleep on the top bunk, though.

We pulled into the station at night, this time, and though I don’t recall the look of the moon, I recall the sign above the station. “Pyatigorsk” (Пятигорск). “Place of five mountains”. Psıkhwabæ. And I recall those mountains peeking over it. I was so, so tiny—age and size (back then5)—and I’d never seen anything bigger than a hill so up close before. Along the contours of the mountains, I could hear the evanesced echo of Martynov’s revolver, and I could sense a thrum somewhere between my bones. Something colossal. Something profound. This was a land where settled my forefathers. My forefathers who fled the Ottoman kılıç, who spoke languages birthed deep in Asia Minor, who were a minoritised Other thrice over on this appropriated soil. Funnily enough, just thirty minutes north by car was where lived my father. My μαυροκύρης (mavrokýris), as I call him.

The three of us (me, my mother, her mother) checked into a sanatorium. In the post-USSR, that’s like a spa resort, but more medicinal. The resort itself was nothing to write home about. In fact, I collected a couple bad memories there, not least of which being the most scarring nightmare of my life (my maternal grandfather had only recently passed away at the time and I was recovering from an open heart surgery (I always thought that timing was poetic)). The edifice was enormous and pallid—bone bleached in the belly of a beast, and I thought narzan tasted terrible even though I so wanted to like it. I didn’t even commit to memory what they fed us, but I’d always had a terrible relationship with food.

And then came the moment of enlightenment.

Beneath the foothill we descended from the sanatorium, a street wound through the massif, trees leaning in to dangle their leaves like glistening smaragdines. I don’t recall too much of the square buildings, only that they led somewhere away into the treeline and up a craggy hill, and that the road itself was dirt—this fine, golden sort. That street is visualised from an odd aerial view in my mind’s eye. It was almost as if I entered an out of body experience, but good, and having DPDR for as long as I can remember, “good” and “out of body experience” is not a common association for me. Perhaps that’s just my brain inflating what I saw whilst descending the foothill.

The day was dry and warm, and I think we assembled for a tour, because then, we ascended a mountain.

Mashuk.

There are several theories to the origin of that name.

Firstly, there’s the idea that it might originate from Kabardian mash for “millet” and ko for “gully”. One legend says that when Qaplan I Giray, a khan of the Golden Horde, invaded Kabardia, ravaging, pillaging, and murdering its inhabitants, Circassian horseman Mashuk, famous for his courage and strength, took revenge on Qaplan for the murder of his bride by Horde warriors. He was martyred by jumping off the cliff instead of being taken hostage or defeated, and so Mount Mashuk is named in his honour. Another story from the Nart sagas—folktales of the North Caucasus—speaks of young woman Mashuko crying over her fiancé Beshtau who was killed by old Elbrus. That’s the story I remember from childhood.

On a fun linguistic note: مَعْشُوقَة (ma‘shūqa), feminine Arabic for “beloved”, has a very similar phonology, having found its way into Persian with معشوقه (ma’shuqe) which is more likely in the modern context to be read as “mistress” than “beloved”, however. I thought it might be cool to see if a cognate existed in Ossetian which is spoken in the Caucasus and is an Iranic language, but “beloved” there is уарзон (uarzon).6

Anyway…

Mashuk was also where Russian army officer Nikolai Martynov shot poet Mikhail Lermontov in their famous duel.

The ropeway dragged us towards the sky, I thought. I had never been so high up, and I was terrified—I’ve always jokingly said that I’m a disgrace to my paternal ancestors who lived in the mountains, relied on the mountains, were protected by the mountains. Only the mountains know our names, and yet here I was, am, cowering from their bosom. The hysterical part was that Mashuk isn’t even 1000 metres tall.

Up so far, the air was vorpal, cutting short my breaths, and it shrieked and snapped at my hair. Yet the strangest thing happened. Standing atop that mountain, I, for a moment, wasn’t scared. I see in my mind’s eye me standing so close to the edge—so much closer than I ever would now, I think. Maybe a part of me fears facing itself, so it keeps back. But the world wasn’t really below me. It was afield. The undulating horizon stretching for miles beyond miles. The volcanic might bubbling beneath the surface of the Earth. And there, just northwest of Mashuk, across the ash and hornbeam thickets, stood the κεφαλαρέα (kefalaréa), the great Beshtau itself. Old Turkic 𐰋𐰃𐱁 (beş)—“five”, and 𐱃𐰍 (tağ)—“mountain”. A five-headed igneous summit. A monument to Earth itself. Upon its foothill rises the Second Athos Monastery of the Dormition founded by Greek monks from Mount Áthos.

This was the Caucasus. The Caucasus where my mavrokýris was born. The Caucasus that sheltered my ancestors and brothers from one of the first and most catastrophic slaughters of the 20th century. The Caucasus that I owe my existence to. It bore down on me, the thread between me and this sacred soil; my veins root into it. The bones of my patríḏa were here, at least those that weren’t lost to the bloodied karst of the Parhar or the black-Black Sea. This was so very almost σιλά (silá)—so very almost return to the homeland. This was enlightenment.

From that day and until the end of our stay in Psıkhwabæ, I’d beg my mother to take me everywhere with her, but she all but committed me to that damn sanatorium, claiming that all those tours “just wouldn’t be interesting” to a little kid. And then we left for home again, whatever “home” even meant, at that point. I still resent her for it all, a little bit. It sowed the seeds of my hireth. Saudade. There’s something about that word when pronounced in Galician that reminds me of Psıkhwabæ. It must be the syllabics. The almost-matching ultima. When I hear “saudade”, I imagine dim light floating along swaying water. I couldn’t explain why if you asked. But the Caucasus Mountains sit between the Black and Caspian Seas, and their veins pump with mineral waters (that narzan I shamefully did not like7), and their vales are soaked with bitter-salt lakes, so perhaps all those disconnected motifs of mine aren’t so baseless.

I cling to aesthetics so fervidly.

I love when places are ugly, dilapidated, industrial. I love when homes are tiny and cosy and gaudy. I love the megalopolis and the dead backcountry both. I hate suburbia and palatial royalty so much I could key a Mercedes (you can’t prove that I have… but you also can’t prove that I haven’t).

I cling to aesthetics so fervidly, and perhaps that is my Achílleos ptérna.

But that’s not the myth on my mind right now. I promise it will make sense (or some backward semblance of it).

Chapter 2: He spoke, let there be en[light]enment

Prometheus was a Titán (Τιτάν). His name comes from promēthḗs (προμηθής), “forethinking”. Seeing the plight of the mortal man, he stole fire from Olympus and gave it to humanity as enlightenment. As civilisation. In all his jealousy, Zeus condemned Prometheus to eternal torture, binding him to a rock and sending an eagle—the emblem of Zeus—to eat his liver. The liver, because it was thought in Ancient Greece to be the cradle of human emotion. Prometheus’ liver would grow back overnight to be eaten again the next day in an endless cycle. The struggle of Prometheus, the site of his everlasting sentence, is said to be located at either the bless’ed mountain Waschḥɛmakhwɛ (Elbrus) itself, or at Mq̇invartsveri, or Mount Q̇azbegi (Kazbek), in Sakartvelo (Georgia). Either way: the Caucasus Mountains.

When I gazed off Mashuk, the wind had shepherded the clouds away, and I sighted Waschḥɛmakhwɛ in the distance, though I don’t recall seeing Mq̇invartsveri. I’m not sure you could.

When I gazed off Mashuk, I saw Prometheus, and he handed me the fire of Olympus. And perhaps we were both Prometheus. Perhaps I remained in those mountains in his stead. In Pontic, “flame” is φλογή (floğí), you know; φλογή also means “sorrow”, “grief”.

And just like that, another summer rolled around and I was in that platzkart compartment again.

I don’t recall this ride, not one bit, but it was towards what I to this day consider the best trip of my life—towards, at least initially, the home of my mother’s childhood best friend.

I don’t want to use her real name, so let’s call her Photine. Like fotiní (φωτεινή). Like “light”. That’s what her real name means, anyway. And I don’t want to reveal where she lives, either, so let’s pretend it’s Apsheronsk. I have never been there, so I’ll keep it in quotations throughout, but “Apsheronsk” supposedly comes from the Tat ab shuran for “salty water”. Very much a cognate of Persian آب شور (âb-e shur). Tat is known as “Kavkazian Persian”. In Gnosticism, water is associated with light. With en[light]enment. There was always something Demiurgic about the nation of my birth.

Whatever. So…

It was late summer, and the knolls and hills of the landscape all but glimmered a resplendent shade of verdure. As the woodland thickened, scaling higher, the mountains in the distance piled in heaps of turquoise and sapphire beneath the sun-scorched sky.

Photine lived in an apartment, one I recall to be a high-rise, but I don’t know how accurate that recollection really is. Photine had a daughter, too. Let’s call her… Evanthia. Why not? We’re on an Ancient Greek theme for this one, I guess. Let’s shorten it to “Eva”, too. Much genesis took place on this trip.

I was still little, maybe seven or eight, and Eva seemed to me so much older with her dyed black hair and baby bat aesthetic. I’d have guessed she was something like sixteen. Looking back, she was probably twelve. Something I do recall is being served a peculiar meal at Photine’s house: buckwheat soup. Now, I was not made to love soup—in fact, I will only eat it if it’s ramen. Yet an extraordinary thing happened this time… I kind of liked it! Photine also had a television with all sorts of channels that ran Western shows! Back where I lived, we only had two or three working channels on an ancient box TV which only ever streamed local. My grandmother still has it. At Photine’s, I caught a few episodes of Power Rangers and H2O in dub, though I had no idea what was going on. There was a cartoon I really liked, but I don’t remember anything about it.

My hair in Psıkhwabæ had been a pixie cut. In “Apsheronsk”, it reached my chin, the hot wind threading it onto its fingers as my mother and I walked the arid streets. Hair holds memories, they say. There’s a lot I could say.

Just about at every corner, there were little stands serving kvass, a type of fermented, low-alcoholic, rye-based drink. And just about at every corner, I’d ask my mother to buy me a cup. Yes, I was a single-digit-aged child drinking something that, supposedly, contains alcohol—generally 0.5–1.0% by weight. Kvass is actually a very healthy probiotic beverage. Anyway, my mother and I went to a bazaar, and “Apsheronsk” was where I first tried that iconic pink cream soda. It’s my favourite soft drink to this day. I think it was that bazaar, too, where my mother bought me one of those coin-decked scarves for “bellydance”. I’d done Turkish-Romani raks şarkı my entire childhood, yet never owned that stereotypical little rag. It’s fun, I suppose, but ultimately quite silly and, in many ways, designed for the Western gaze. I’d never wear one now. At least it was as pink as the cream soda. I loved pink.

Sometime during our trip to “Apsheronsk”, we visited Photine’s parents who grew squashes and grapes in the mountains. That was my first experience of humidity—a sticky, balmy heat I now know like a pervasive ill. There’s a photo of me in that squash garden holding a comically-Elizabethan hand fan, my face positively haunted, and I think it’s really funny; I look like a stonkered baby animal for literally no reason.

But that wasn’t the place I want to take you.

We boarded a train—not an overnight one—to Shachɛ (Шъачэ). Or “Sochi” (“Сочи”). Where they hosted those goddamn winter Olympics. You remember. On stolen land? On soil sown with the bones of its people? Somewhere near a Shachɛ beach, Evanthia plucked a magnolia flower. Neither Photine nor my mother were pleased with her.

We did not stop there, however.

We walked down a wide dirt path cleaving the cliffs, beneath oppressive heat, to the border crossing. Photine and my mother seemed to find something hysterical about the trek. It was my and Eva’s turn to be not well pleased. We were just tired little kids.

Over the border was Apkhazeti. “Abkhazia”.

It’s a partially-recognised state occupied by the RF, its de facto government existentially reliant on the Kremlin. Throughout the separatist wars of 1992–3 and 1998, thousands of Georgians were ethnically cleansed from Apkhazeti with the help of the Russian state. Armenians, Caucasus Greeks, and opposing Russians and Apsuaas were killed alongside, though the primary motive was anti-Georgian racism and land occupation. It reminds me of Septemvrianá. I’ve talked about it before.

Apkhazeti will always be Sakartvelo to me.

And I have no idea why, but that’s where we were. In a hostel filled with strangers, yet that place might be my warmest memory. For whatever reason, I ended up getting the cleaner’s room? In my mind, it’s the tiniest thing on Earth, just big enough for the bed, with no windows that I remember besides an aperture for light high up on the door. And yet my memory doesn’t cool one bit at the thought of it. I wonder if that’s why I love tiny rooms and places so much now; I jokingly call it “claustrophilia”. The hostel also had a second level with a balcony that I don’t remember ever ascending, and on the ground floor, chairs and benches stood around a courtyard. I think a fireplace was there somewhere, too.

I don’t picture many of the faces, but there was this one Mingrelian man, a little older than my mother, I see with perfect clarity. He had the blackest hair and the fullest moustache I have ever seen. He would sit out in the courtyard with other guests, and they’d just talk. Just talk. He never talked to me, but he talked to my mother. I wonder what they talked about.

Apkhazeti was where I tried blackberries for the first time, in this tall plastic cup my mother bought for me at the bazaar, and I still buy a punnet here and there for myself. My mother doesn’t understand why I like them so much when “they don’t have an aroma—not like raspberries”. It’s not about the aroma. It’s about the fact that I cling to aesthetics so fervidly, all to chase the feeling of times gone by. And the bazaar is such a familiarity for me, with its tarps and spreads of fruit and clothes and hubbub. I’d gone to bazaars with my grandparents since all but birth; I’ve never even used the word “market” in speech after learning English. At that Apkhazeti bazaar, Photine and my mother bought a watermelon, but when they cut it open, it was basically white with unripeness, even though they swore they did the tap trick (iykyk). There were palm trees there too that I hadn’t seen before, not even in “Apsheronsk”, and Garga (გაგრა) had water clear as glass and a shoreline of only pebbles. To this day, I consider that beach somewhere along the Georgian coast to be the best one I have ever experienced. I also just hate sand (coldest take in history). Though it wasn’t Gagra where we stayed because I remember needing to catch a marshrútka there from the hostel; I remember how it weaved over and around the verdant mountainside.

Sakartvelo was so very almost σιλά (silá)—so very almost return to the homeland.

I would not return to Apkhazeti today, not when I’m so cognisant of colonial reality in my barely-adult age, and I don’t think anyone should be going there, especially for frivolities. It would be like willingly going to the West Bank, or Qırım. But growing up is its own enlightenment. Φλογή (floğí) means both “flame” and “sorrow” in Pontic, and Prometheus gave fire to humanity.

When we left Sakartvelo for “Apsheronsk”, and then “Apsheronsk” for the north, it had just hit autumn. I vividly see myself watching an episode of that one cartoon I don’t recall anything about, the wall-sweeping window to my left opening up to a scene of bucketing-down rain. Seconds after my mother and I boarded the train back north, it started to hail.

And so, I think again about “home”. I write about it a lot.

Almost daily, I contend with being an immigrant and with the subject of colonialism, not just in terms of academic-adjacent political writing, but within my own multiethnic identity. Colonised and coloniser. Persecutee and genocidaire. Traditional custodian and settler. Identities I wear, and those that dwell within but which I do not claim due to profound disconnection. Sometimes, they interrelate in ways not most obvious to the observer. But none of it is obvious to the observer. Some of it is hardly obvious to me, and I’m the one doing the work.

Earth Hagiography is an entire book I wrote filled, in large part, with poetic lamentations about displacement and ancestors and urheimat. Cradleland. As I learned from Lilly ջան, someone whose prose poetry helped me learn to read the Armenian alphabet: penned from «գրողի ծոցը» (groghi dzotsə). The writer’s bosom, or Death’s embrace. Գրող (grogh) is both “writer”, and a spirit of death in Armenian folklore who scribes the sins and virtues of humanity in a book to be read by God upon judgement. From the cradle[land] and back again. I wonder what Prometheus would say to a grogh.

Chapter 3: from the writer’s bosom to Death’s embrace

Teenagehood and an immigration from my birth country later, and I haven’t been back to the Caucasus in years. The separation is indeed hireth. Saudade. I consider it a sickness. Whenever I ride trains, I search for glimpses of a country I knew since birth, a soil I was ripped from, the land that both saved and buried my forefathers. I’ve even started to look out for silhouettes of the capital I despise. It brings me to tears at the most inconvenient instances. It’s like my body is over there, but it’s not.

And I’ve been gnawed at by wanderlust.

I never thought I’d be one of those restless people, but sometimes I’ll board a train or bus and simply sit as it takes me wherever. I tell my friends to meet me far away just so I can take public transport there (I do not drive, and plan to do everything in my power to never have to). I leave the house just to do it. In February, I had a taste of abatement when I flew out for a political conference, but it didn’t mollify.

I needed to see the Caucasus again.

I needed to do it because I feared.

I’ve written poems about the Caucasus; I’ve written poems about Armenia. And after Artsakh, its loss to invaders, I’ve been in pain. I fear that there might not be an Armenia much later than this time. It’s a horrifying thought I don’t want to entertain, that a civilisation so ancient might be lost in my lifetime, that I might lose even more of my siblings, but Azerbaijan’s terror knows no bounds, and what is Western-defined “peace” if not a legitimisation of genocide?

So I booked a flight.

To Yerevan.

It was a little rash and highly financially irresponsible, but I was being suffocated and I needed to breathe in. I needed to run away from something. From nothing. From everything. From գրողի ծոցը.

I needed to chase a feeling of times gone by.

I posted a vlog-esque video about my solo adventure to my basically-defunct YouTube channel, so I won’t recount what I did beat by beat as in prior chapters, but I’ll tell you what I felt being back in the Caucasus Mountains. What I felt so very almost making σιλά (silá)—so very almost returning to the homeland. Though I should also clarify that the title of the video was mainly for the bit. There was nothing unexpected about my departure, and I did not move away (disappointingly). Also, the city I currently reside in is quite literally nearly 100 times the size of Yerevan (in km²) yet more than 20 times younger with nothing to look at.

My trepidation in the months leading up to the flight was unprecedented, and on several occasions I almost cancelled my tickets. I kept getting cold feet, I catastrophised beyond reason. Anything could go wrong; I’d never travelled alone internationally before. But I think I feared never going more than I feared whatever might befall me if I did. Some days before my trip, wracked with anxiety, I sought out an article about travelling by a woman with depersonalisation disorder. Existing with DPDR myself, I’ve never been able to quite express this sensation of disconnection from the Self, and I felt comforted by the essay.

“[…] any kind of change can send me into serious shock. I have been much calmer about moving than I thought I would. But the moment that I’m alone in a strange apartment […], I will begin to panic. I know this because I know how my brain works by now. My thoughts will go into overdrive. You said this wasn’t really happening! What are we doing here?! Is this a dream? It won’t be easy, but I’ll have to cope with the panic until it subsides. But then I run into another problem. I will slip back into the grips of my disorder, as I always do. Sometimes I see my depersonalization as a coping mechanism. It’s a comfortable blanket to hide under, a familiar state of apathy […]

I may be holding my passport, but my brain tells me I’m not going anywhere […] Since there’s this fog over everything, keeping me from connecting to any event in my life, my brain can pretend anything it wants. It tells me there are no consequences, no reason to focus, because none of this is happening anyway […]

Being in the moment is nearly impossible for me. If you’ve ever found me socially awkward, you’re right. I am. This is partially because of the depersonalization telling me that my voice is not my own. It makes me feel very uncomfortable when speaking, like I’m an actor and I’ve forgotten my lines.”

In truth, though, I think I eventually numbed out to all the anxiety so much that, on my departure day, I didn’t feel anything anymore.

And on my departure day, it rained, thunder ripping asunder the sky and levin fulgurating as the night cast down. It would rain for half of my week away. Both here and there. My El Salvadoran housemate, a 70-year old man, told me before I left that the outdoors were good for the youth. That sitting inside four walls stifled inspiration. It was basically a blessing on my way. Su gibi git, su gibi gel. Come like water, go like water.

There was a poetry to riding the bus to the airport train, then the train to the airport itself, in the pouring rain, listening to Mājida r-Rūmi’s Kalimat, watching the orange glow of headlights and neon scatter through droplets. I felt a flicker of that whimsy of wanderlust again. Su gibi git, su gibi gel.

And I adore airports.

A constant state of dissociation—DPDR, as it were—is how I live my life, and the liminality of an airfield is the one thing that doesn’t feel as if it clashes with my existence.

I waited a good three hours for boarding out of anxiety over crossing customs, and the whole time, walking the halls of the international terminal, I cycled through excitement and absolute fvcking terror. What am I doing? Where the fvck am I going? By myself? I should also confess here that I never told my mother about this endeavour, and at the time of publicising this “memoir”, I still haven’t. But it was too late, at that point. I was about to be trapped in a giant flying bus for 14 hours. And so I was.

International travel is a timewarp: you think days, weeks, have passed, when it’s been less than 24 hours. At least I do. On a trip so long, time blurs. And how much do time zones even matter when you’re flying through them, warping them? I’m sure there’s an irony there.

My 14-hour layover was in one of the Four Horsemen of the Gulf. You know the ones. But no, not UAE. Let me not give it too much space, because both soon and not, I boarded the plane to Yerevan: my final port of call. It was half empty, so much so that I was the only one sitting in my row and the little flying bus had parked itself somewhere in the middle of the desert airfield—a bus ride from the gate, taking its passengers in by stair. A good quarter of the passengers was diaspora, speaking to their children in macaronic Armenianglish. It was obvious everyone aboard was going home.8 Everyone but me.

I landed at midnight and my taxi ride from Zvartnots International Airport to the guesthouse I’d be staying at didn’t quite piece into a cohesive reel in my memory, but what struck me was how full of light the city was. Illumination filled even the most nothing street, and all the landmarks glowed this candent orange-gold like saffron oil. Like φλογή (floğí). It wouldn’t register to completion until I returned to my host country and couldn’t see fvcking sht looking out of the bus window at night.

The next day, or I suppose later that day, I woke up in Yerevan.

The guesthouse was a ghost town, though with a few signs of life, like a green bottle of mineral water beside a bagged loaf of dark bread in the dining room, and I was starting to panic. A new, unfamiliar place, no guarantee I’ll always be understood, reliance on taxis due to not being local, and a massive pit of fresh, panging anxiety. What am I even doing here? I felt like I’d disappointed myself, even though I literally hadn’t done anything yet. Maybe that was where my disappointment lay. At least my international roaming was working!

At last, after speaking to the guesthouse owner, a pleasant, clean-shaven Hayots man who was very intrigued by the country I’d flown in from (not the Gulf one), I sucked it up called a taxi (via the gg app instead of Yandex), and it whizzed me into the city. I should take a moment here to express my admiration for Armenian drivers. I’d never get into a taxi where I currently live despite the supposed “safety” of this Western sub-empire, yet my experience of Yerevan taxis was wonderful and the drivers made me feel entirely safe and welcomed.

My first ever landmark was the Sasuntsi Davit Railway Station, named after Davit of Sasun, «Սասունցի Դաւիթ», a hero of an epic, a vanquisher of invaders. Lilly ջան’s forefathers are Sasuntsi. Of a land invaded.

I needed to buy a ticket to Tbilisi. A ticket onto the overnight train.

After I did, I just walked.

The city had so much character and personality—was so lived-in. Purposeful. It knew what it was and its people did too. This was a land that remembered everything. A land that had a lot to remember.

They say Yerevan (Երևան) comes from Էրեբունի (Ērebuni), rooted in the vetust Urartian 𒌷𒅕𒁍𒌑𒉌 (er-bu-u-ni). “Conquest”. A city that had been conquered so many times, touched by so many hands, yet for almost three thousand years beat with the blood of Հայք (Hayk’) all the same. Under the Soviet Likbez reforms of 1922–40, Երևան became Յերեվան. -ևան (-yevan) became -վան (-van). Like Van. Like the imprisoned country. Like mockery of a land taken, not sold. A land invaded. Yet they continued calling this ancient city «Эривань» (“Əriván’”), from “ایروان” (“İrəvan”), long into the 1970s. What the thieves still call it, making up stories.

But the USSR knew a thing or two about selling Armenian land.

It rained my first few days in Yerevan, in the lead-up to my train ride north. Անձրեւ արտասուաց (anjrev artasooats’). “Tear rain”; “a flood of tears”. I cry a lot when I’m nostalgic. Saudadic. The rain made the streets contemplative, and there was something so familiar about Yerevan—like I’d been there before.

I eyed up the stalls at Vernissage Markets and sojourned with cats in the empty courtyard of Blue Mosque and scaled all 572 steps of the Cascade Complex (thrice) and spoke to an Artsakhtsi woman in the candlelit halls of Saint Gregory the Illuminator Cathedral. She told me her husband died in the war. At the masjid, lilacs grew; I hadn’t seen lilacs in years.

One rarer way of saying “lilac” in Armenian is հազարագեղ (hazaragegh), from Persian هزار (hazâr) for “thousand”9 and Old Armenian գեղ (gegh) meaning “beauty”. “A thousand beauties”. Fitting! Lilacs symbolise first love and the arrival of spring, both equally fitting. And the most absurd thing happened to me at the bazaar! Half-dissociated as I’m wont to be, I loitered about when I got approached by an Irânian man. He looked me dead in the eyes, and started speaking Persian at me, seemingly convinced on God’s name that I understood every word he said (I, in fact, understood no word he said). After some fumbling, me and the lady at the stall figured out that he wanted to know what material the jewellery she sold was made of, but being taken for a Persian at a Yerevan soūq, so much so that the [potentially] actual Persian felt sure enough to speak Pârsi to me without even asking, definitely wasn’t a prediction of mine. Also, I saw a man and his son who I’d been on the plane to Yerevan with at the Cascade! I don’t think they recognised me (if they noticed me at all).

When I returned from my day trip to Sakartvelo (which I’ll speak on in a minute), I made a pilgrimage to Tsitsernakaberd, the Armenian Genocide Memorial dedicated to the 1.5 million victims of one of the first mass slaughters of the 20th century.

I ventured there on April 20th, but April 24th was the decimation’s 110th commemoration.

To say standing at Tsitsernakaberd overwhelmed me with emotion is an understatement. They weren’t being metaphorical when they said that crying fogs up your [sun]glasses. For some reason, I hadn’t believed that was a real phenomenon.

The stone complex of Tsitsernakaberd, crowning a hill embowered in woodland greenth, was saturated with grief, overlooking Ararat in pining to reunite, the air leaden and algid even under the vernal April sun. A brutality to its form, and at the centre of the twelve pylons of the Sanctuary of Eternity, twelve for each of the provinces where Armenians were put to the kılıç—a flame burning; a nucleus ablaze; a beating heart. Around it: a circle of flowers laid, amidst which I placed a dandelion. I learned it from Circassians, that a dandelion’s seeds fly away when harmed, root in far-off lands and grow anew, again and again. Poet Dínos Christianópoulos supposedly said something alike, too, “They tried to bury us, they didn’t know we were seeds”. The extermination of Armenians coined the term “genocide”; the extermination of Circassians, some half a century earlier, coined the term “ethnic cleansing”. But I should like to see any power of the world destroy this race, this small tribe of unimportant people […] See if they will not live again. See if they will not laugh again. See if the race will not live again when two of them meet in a beer parlor, twenty years after, and laugh, and speak in their tongue. Go ahead, see if you can do anything about it.10

I wandered the structure in silence, a ghost, for a good two hours, I’d wager, and contemplated—it wasn’t just the rain that called for it in a city so ancient.

I’m glad to have made the pilgrimage to Tsitsernakaberd alone.

I’m glad to have made my trip back to the Caucasus alone. Itself a pilgrimage. Itself silá.

But before that, I boarded the overnight train from Sasuntsi Davit Railway Station in Yerevan to Tbilisi. To Sakartvelo.

I ended up in a standard four-person coupé with three Brits, a pair travelling together and one lonesome backpacker. Conversation with them was agreeable, but strange, even stilted—a Western cadence to their comportment that I found myself not mirroring. Where I gazed out of the window and watched the landscape flicker by in silence, they talked among themselves, only really glancing to marvel at the rolling mountains swathed in fog, or comment on how much “better maintained” the Georgian countryside was. It felt odd, because I grew up in hinterlands “maintained” far “worse”—in a village where six people lived then and now merely one. But I suppose we were fundamentally unalike; I suppose that train wasn’t exactly silá for them. But I think there was some fate at play, too: the conductor simply chose not to speak to them, and instead had me translate. And that wasn’t even the only time I had to interpret for a TERF Islander that week! They also didn’t really know all the little minutiae of an overnight train, like the fold-out steps or the best technique for climbing up to the top bunk (although my grandmother never really let me sleep up there when I was little for fear of me falling off, she let me sit there in the waking hours because I’d just pester her that much over it).

This time, on my own and debatably an adult, the top is the bunk I chose, even when the lonesome backpacker offered to trade spots in an act he probably deemed gentlemanly. Even on the train back to Yerevan where it was just me and a quiet Armenian man with nervous energy in that same four-person coupé.

I started crying up there. I cry a lot when I’m nostalgic. Saudadic. And I cried a lot! Embarrassingly, actually. I’d so long chased the feeling of times gone by, and there I was, the tuh-tun, tuh-tun as the old locomotive cut through mountains and crossed the backwoods of the Caucasus. This is where silá rooted in the deepest, to the marrow. I’d been there before—I’d quite literally been in Sakartvelo before. And I’d spent my entire childhood in overnight trains, across the fold-out table from strangers. It suddenly felt normal gain after years of my existence clashing with the world like a transplanted organ. The only thing I didn’t have with me this time was a bag of pistachios, and quite frankly I’m kicking myself over it; I don’t believe anything in this world “isn’t that deep”.

But it still wasn’t that train. It would never again be.

That train doesn’t run anymore.

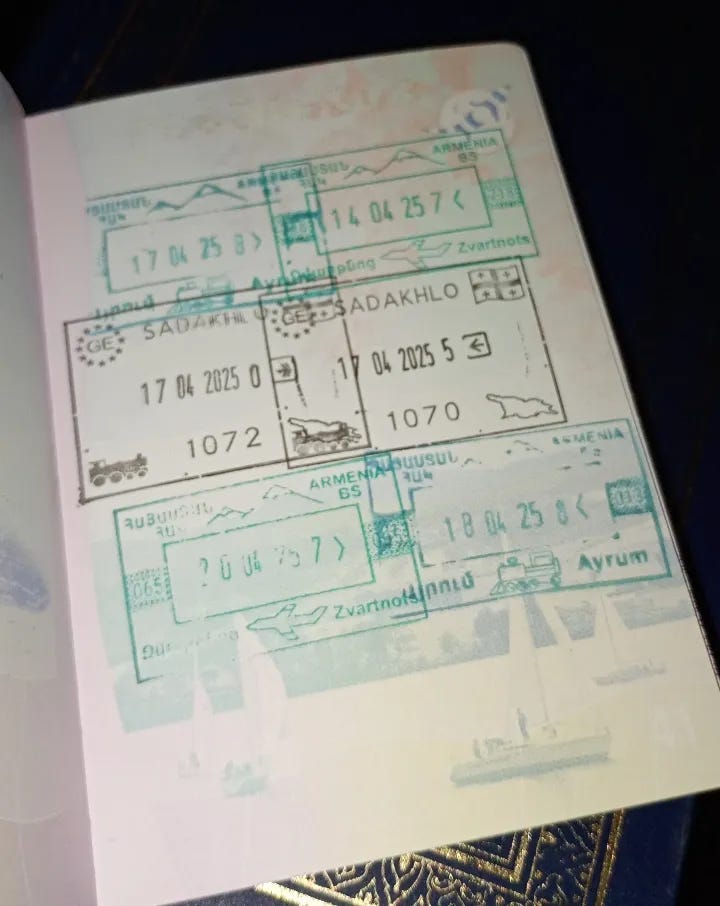

They woke us up at somewhere near 4 AM for border crossing, after which none of us went back to sleep. I watched the sun come up and scatter the fields, the mountains, the rising commieblocks as the train pulled into the city. The photograph at the top of the essay was taken from the train some time after the border had been passed.

And then we were out. I never saw those strangers again.

Tbilisi (თბილისი) was once T’pilisi (ტფილისი), from ტფილი (t’pili): “warm”. There’s another, historical, name for Tbilisi, to boot. Tiflis. After the old Arabic تِفْلِيس (Tiflīs), but ultimately itself from T’pilisi. A doublet. Some languages maintain this roundabout etymology to this day, like the Greek Τιφλίδα (Tiflíḏa) or Turkish Tiflis.

A four-hour tour awaited me first thing upon my arrival, our guide a young-ish man some might call a tad overzealous. To me, it was heartwarming that he had a country he could be that proud of and love so deeply. As I lamented in my previous essay, I’m stuck with a pair of absolute disgraces.

The marshrútka weaved us over and around verdant mountainsides from Tbilisi towards Mtskheta (მცხეთა), the old capital, situated some 20 km away at the confluence of the clay-rich Aragvi and Kura/Mt’k’vari Rivers. “Mt’k’vari” is its Georgian (Kartuli) name, whilst “Kura” is Mingrelian, a semi-mutually-intelligible language with my dear Lazuri. From Svet’itskhoveli Cathedral—“Living Pillar”—at Mtskheta’s heart, where the sacred robes of Yēshū Mshīḥā are said to be buried and through which bells pealed that morning in a canorous Paschaliá cantillation, we were soon taken even higher into the mountains.

Jvari Monastery perches upon an eroding cliffside overlooking Mtskheta.

Up so far, gelid wind beat tears from my eyes, my ears popping as I breathed it in, the air vorpal, shrieking and snapping at my hair. Hair holds memories, they say. I think that’s why I veil it, these days (I don’t believe anything in this world “isn’t that deep”). And I was right, you know. I didn’t get very close to the edge—not as close as I recall standing atop Mashuk.

I lit a candle in the one-and-half-millennium-old innards of the fortress. I don’t quite know what I lit it in honour of.

After the Chronicle, the unfinished grand monument overlooking Tbilisi “Sea” (a massive artificial lake) carved with images from Georgian history and Biblical stories, I got dropped off near the capital’s centre where I was alone again.

In Yerevan, I greeted everyone in Armenian, and so I was immediately spoken Armenian to under the assumption, I figure, that the meagre knowledge displayed bespoke a deeper one. But I could tell some people, here and there, were trying to work me out. I’m well aware I don’t “look Russian”, but I’m not daft to think I share the unique phenotype Armenians have (unbeknownst to myself, I apparently look Persian enough to just be spoken Pârsi to, I guess!). In Sakartvelo, however, I noted people assume I’m Georgian. Every time I’d get asked to that effect, and I said no, my assertion would be met with surprise. This fact, though, meant that I went unnoticed as I made my way about. It felt liberating to not be seen. To be anonymous, chronicling. I never feel like that. Normal. Getting strangely stared at is a natural part of my day.

Tbilisi was once T’pilisi, from ტფილი (t’pili): “warm”. It was, too. A cradling, amniotic sort of warmth that doesn’t exist in my host country. I like to think it’s because the ozone layer is actually somewhat intact in Sakartvelo. A Svan acquaintance had let me know that the metro in Tbilisi can be paid for with a Visa debit card, so that’s what I did. The underground metro is another one of my great loves. Nothing quite compares to the buzzing squeal of the train pulling up and the wind it stirs on its way past. It’s a language in itself. I took the Akhmeteli-Varketili Line to the Museum of Joseph Stalin’s Underground Printing Press, but I never actually went in, just as I never went into the Lusik Aguletsi House-Museum and Art Cafe in Yerevan. There remained an anxiety I couldn’t cut through. It’s the same anxiety that made me unable to enter restaurants in Yerevan, forcing me to grocery shop to feed myself. But I’ve always had a terrible relationship with food.

You can tell Tbilisi is more modernised than Yerevan and significantly bigger—more than thrice the size (in km²). And yet it was nowhere near as walkable. Whilst Yerevan’s streets are marked by pedestrian crossings every couple blocks, if more, it wasn’t seldom that I needed to find a gap in traffic to traverse a Tbilisi road. To be clear, it didn’t even hold a candle to the misanthropic Hellscape I live in—to even remotely compare to that, you’d literally need to be an interstate highway—but with Yerevan for a backdrop, the difference was noticeable.

Nevertheless, I strolled the streets of Tbilisi and pondered again. I didn’t even go inside the Holy Trinity Cathedral. I couldn’t tell you why, but maybe it was the gilded structure’s disorienting splendour. The woman* was too stunned to speak.

Once the sun began to melt into the highlands, I commenced my move back to the station where the train I’d arrived on that very morning awaited its evening departure.

En route, I passed a bazaar, and it was arguably the most familiar place I visited along my journey. It was crammed, dusty, enormous, effervescent with its tarps and spreads of fruit and clothes and hubbub. And it struck me with the most potent feeling of hireth. Of a time gone by. A childhood resurrected. I’d gone to bazaars since all but birth, after all. It’s such a familiarity for me. I’m thinking I should’ve looked for blackberries to buy, like Apkhazeti again. Apkhazeti will always be Sakartvelo.

It deserves to be stated here that I managed all those hours of both long-distance transit and wandering on 1(one) Imeruli khach’ap’uri and 1(one) churchkhela, on no international roaming since it never kicked in once I entered Sakartvelo for some reason, and somehow it worked! Then again, churchkhela was historically carried by warriors trekking impossible distances through the Caucasus, so I’m hardly surprised that one managed to sustain someone as aggressively lacking muscle mass as myself. Interestingly, both while buying the khach’ap’uri and the churchkhela, I was doing it surrounded by other people who also were, as opposed to being—or perhaps just feeling—completely on my own like in Yerevan. That might very much be a “seasoned traveller” leaning curb though, and a seasoned traveller I am not (I did order the khach’ap’uri in perfect Georgian though!).

Finally, it struck 8:30 in the evening, and we were Yerevan-bound. As I’d mentioned, I was in a four-person coupé with an Armenian gentleman, the train being far less populated in the other direction, yet I still took the top bunk. It was interesting that both Georgians and Armenians told me that the other one is a colder people, less personable. I suppose all our worlds are informed differently. And I think I knew somewhere in the back of my mind that I wasn’t likely to handle a platzkart well as a fully-conscious grown-up, hence I bought coupé tickets both ways.

As the train raced back to Sasuntsi Davit the next morning, due to arrive at around 7, I watched Ararat burgeon on the horizon. The resting place of Noah’s Ark. Masis (Մասիս). “Ağrı Dağı”. Ağrı means “pain”. Isn’t that funny?

Seeing Ararat from the overnight train was like seeing Waschḥɛmakhwɛ after the wind shepherded the clouds away, or perhaps beholding that one Eréchthion caryatid trapped in the British Museum, separated from its sisters. An ancestral heirloom displayed in a robber’s vitrine. Taken, not sold. You deserve to be home, I thought.

That was the day I went to Tsitsernakaberd.

That was my second-last day in Yerevan.

The next day of walking through the sunny city one final time came and went. The taxi to the airport, driven by the loveliest older gentleman, Armen, came and went. The flight, the layover, the utterly horrific 14-hour second leg, came and went.

On my flight out of Yerevan, as I buckled in, it had started to rain again. Su gibi git, su gibi gel. And I cried, because of course I would.

Funnily enough, remember that man and his son who I’d been on the plane to Yerevan with that I mentioned noticing again at the Cascade Complex? Well, a guy who had been on my train from Tbilisi to Yerevan ended up on my flight from Yerevan to the Gulf!

In the end, here I am, back and writing, or trying to.

Chapter 4: that which is untranslatable

I’ve been saying σιλά (silá) a lot. Return to the homeland. It more wordily means a few abstract things, but notably “return of expatriates to their homeland”, though less in a repat way and more in a… displaced people way. In Turkish, sıla is used in the same sense. The act of reuniting with loved ones or homeland, and by extension one’s dearly missed birthplace, after a long time. Both are ultimately from the Arabic verbal noun صِلَة (ṣila), “connection”. Σιλατζής (silatzís) is one who makes such a return.

But I find the use of «σιλά» as a de-facto particle to be even more fascinating.

I should point out here that a lot of the following is fruits of my personal research and may not be accurate to all dialects (and it wouldn’t be). It’s just something of a special interest.

Σιλαλέα (silaléa) is a thick seam, as in stitching. “Sewing with thick stitches” is σιλάλιν (silálin), “[I] make a thin seam” is σιλαλίζω (silalízo), “[I] sew roughly” is σιλαλεύω (silalévo), and “to sew with a seam” is σιλάλωμα (siláloma).

Λεύω (lévo) is supposedly Ancient Greek for “[I] kill by stoning”, whilst λίζω (lízo) means “[I] play”, but finds its root in Proto-Indo-European *leyd-, meaning “to let go”; “to release”. Λωμα (loma) may be related to Ancient Greek λῶμᾰ (lômă) for “hem [of a robe]”.

Repatriation is entwined with needlecraft, with creation, and yet how easy it is to weave it into violence. Into loss.

Κεφαλαρέα (kefalaréa), what I’d called Beshtau, means “the highest part of the landscape”. It wasn’t really, but viewed from Mashuk, Beshtau certainly seemed bigger than the distant Waschḥɛmakhwɛ. Κεφαλαρέα comes from κεφαλόπ’λλον (kefalóp’llon) for “head”. The Gimişhaná/Gümüşhane Pontic κεφαλοκοψία (kefalokopsía) combines κεφαλόπ’λλον (kefalóp’llon) with κόψιμον (kópsimon). Literally “head-cutting”. In use: “a mass slaughter of people”. Genocide. The natural world is sacred to indigenous populations, mountains being among the most precious. Beshtau was once bathed in the blood of the people of its soil, when the Russians committed κεφαλοκοψία in 1863. The event that coined “ethnic cleansing”. To this day, the Circassians can hardly make σιλά, most remaining in exile far, far away. Ironically, most of them in Türkiye.

Those are all Pontic words. Upon research, none of them exist in Modern Mainland Greek, Νεαελληνικά (Neaelliniká),11 the “Greek” most think of when hearing the word. The “Greek” I choose not to align with. I find it a worthy thought to pause upon, that Greek is touted as one of the world’s oldest languages, and yet Neaelliniká must use so many words to say what Rumca/Pontiaká can in one. Like how σαβανίστρα (savanístra) is a woman whose profession is to shroud the dead, or χαλκοπρόσωπος (chalkoprósopos)—“one who has eyes green like the rust of copper”. Or that μαυρογεννώ (mavroğennó) is literally “black birth”, yet is used to say “[I] give birth under bad omens”. In Pontic, one way to say “coffee” is μαυροζώμιν (mavrozómin). “Black hole”. Like how the Armenian սուրճ (soorj) is “black water”, at least by folk etymology. We were always siblings. And neither of us can make sıla.

I talked about it all before, in Laz Wisdom. About p̌ap̌upeşi ziťape, “maternal grandfather’s words”.12 Proverbs. About the richness of Lazuri and Rumca. About these untranslatable words.

It’s like hireth. It’s like saudade. It’s like Mashuk. Ararat. From groghi dzotsə. Enlightenment through suffering, though ağrı, like Prometheus—condemned never to come home.

It’s like chasing the feeling of times gone by.

~Sfar~Ⓐ🧿֎⨳

Portuguese and Galician word.

Cornish word. Cognate of the better-known Welsh hiraeth.

There will never be anything “European” about a region so deeply intertwined with West Asian heritage, culture, and linguistic legacy.

Ӏуащхьэмахуэ; Qebertaibze/Kabardian. Aadəɣabzɛ/Adyghe is Waschḥɛmafɛ (ӏуашъхьэмафэ). Elbrus (Эльбрус) in Russian, and Miñi tau (Минги тау) in Qaraçay-Malqar/“Karachay-Balkar”.

I am now 177 cm (5’10’’ in fake units). Long legs to run away from the Russians and Ottomans ykwim (only I’m allowed to make that joke).

For those who want to listen to how Ossetian sounds:

Keep in mind that I was six at most and so picky I didn’t eat eggs, cooked vegetables, or white bread (not that I eat them these days either…).

I’m sure not eVeRyOnE, but walk with me here—I’m trying to be narratively compelling!

Since I’d brought the subject up before, this word actually did find its way into Ossetian! As ӕрзӕ (ærzæ).

Full quote by novelist and playwright Vilyam (William) Saroyan (Վիլյամ Սարոյան) in English and Armenian:

“I should like to see any power of the world destroy this race, this small tribe of unimportant people, whose history is ended, whose wars have all been fought and lost, whose structures have crumbled, whose literature is unread, whose music is unheard, whose prayers are no longer uttered. Go ahead, destroy this race. Let us say that it is again 1915. There is war in the world. Destroy Armenia. See if you can do it. Send them from their homes into the desert. Let them have neither bread nor water. Burn their houses and their churches. See if they will not live again. See if they will not laugh again. See if the race will not live again when two of them meet in a beer parlor, twenty years after, and laugh, and speak in their tongue. Go ahead, see if you can do anything about it. See if you can stop them from mocking the big ideas of the world, you bastards, a couple of Armenians talking in the world, go ahead and try to destroy them.”

«Կուզեի տեսնել աշխարհում որեւէ ուժ, որ կկործանի այս ժողովրդին, անկարեւոր մարդկանց այս փոքր ցեղը, որի պատմությունն ավարտված է, պատերազմները՝ կռված ու պարտված, շինությունները՝ փլուզված, գրականությունը՝ չկարդացված, երաժշտությունը՝ չլսված, եւ աղոթքները՝ լռած։ Դե կործանե՛ք։ Ասենք թե նորից 1915-ն է, իսկ աշխարհում՝ պատերազմ։ Կործանե՛ք Հայաստանը։ Տեսեք՝ կստացվի՞։ Տնահան արեք ուղարկեք անապատները, թողեք առանց հացուջրի, հրդեհեք տներն ու եկեղեցիները։ Տեսեք՝ նորից չե՞ն ապրի, նորից չե՞ն խնդա։ Տեսեք՝ նրանց ցեղը չի՞ հառնի, երբ քսան տարի հետո երկու հոգի հանդիպեն գարեջրատանն ու ծիծաղեն ու խոսեն իրենց լեզվով։ Դե՛, տեսեք՝ մի բան կկարողանա՞ք անել դրա հետ։ Տեսեք՝ կկարողանա՞ք արգելել, որ նրանք ծաղրեն աշխարհի մեծ-մեծ գաղափարները, շա՛ն տղերք, որ երկու հայ խոսեն աշխարհում, դե՛, փորձե՛ք կործանել նրանց։»

I’m perfectly aware that it’s two words.

For those who want to listen to how Lazuri sounds: