In Lazuri, the language of the Laz people indigenous to modern-day occupied northeastern Türkiye, the term for “proverb” is p̌ap̌upeşi ziťa, literally “maternal grandfather’s word”.

These have been sombre times.

The brutality we see unfolding before our eyes is draining, more so when it’s your or your sibling peoples bearing the brunt of genocide and systematic oppression, and all the more so for those actually experiencing it.

Despite the overwhelming stress of my final [ever!] university semester, compounded with the all the terrible pain of the world, I’ve been secluding myself. Notwithstanding, I’m keeping my ancestors close; holding space for them to listen and speak to me through water divination, music, and other spiritual communions.

I won’t go into my ancestral practices here, as it is something I find rather personal and only willing to deeply discuss in person with those enthusiastic to partake. Opening an energy portal isn’t light and magical like the Occidental Wiccan girlies would have you believe.

Instead, I would like to impart unto you, reader, some Laz ancestral wisdom I’ve been taking solace in lately, not only to centre a wonderful, earth-doting culture and unique language forgotten or outright unknown by too many, but to perhaps cast the tiniest ray of hope onto these black days of ours. I know how much pain we are all in.

I think a quick pronunciation guide is required before we proceed:

For example, coxo (“name”) is pronounced jokhó.

A lot of this is difficult to explain to Anglophonic (and honestly most non-Kartvelian) speakers, seeing as Kartvelian languages have t and t’/ť, k and k’/ǩ and q, p and p’/p̌, ç and č and ç̌ which are all similar to their respective partner but not quite… Ultimately, the most novel sounds like ğ and c have been delineated enough for you to understand moving forward.

Words from the Earth

Let me tell you where this “black days” phrase I’ve been reiterating comes from.

„Çkin kianas mince vauns; vai çkini uça dğasu…“

“Our country has no-one to protect it; pity our black days…”

It is a proverb about occupation. About expulsion of a land’s traditional custodians—something Anatolia is all too familiar with. A land without its ancestral peoples withers. We see it with the mass bushfires across indigenous country wherein colonial governments ban controlled burnings. We see it in the poisoned rivers and barren soil of stolen lands.

Across Pontos/Lazica, modern day occupied northeastern Türkiye, the term “black”, especially in Pontic, almost never seems to exist literally. Observe:

κορωνέας (koronéas): “black as a raven”, but also “miserable”.

μαυροζώμιν (mavrozómin): “coffee”, but also “black hole”.

μαυροσύρω (mavrosýro): literally “to drag black[ness]”, meaning “to suffer”.

μαυροχαίρεμαν (mavrohéreman) = “joy for a short duration”.

μαυροχωμία (mavrohomía) = “a place with black soil”, but also “grave”.

Even the word I use to refer to my father, μαυροκύρης (mavrokýris), meaning “grieving father”, translates literally as “black patriarch”.

None of these words exist in mainland Greek, which tends to be a trend—so many singular Pontic words require an entire sentence of mainland Greek for a definition, like αγγλόφρυδος (anglófrydos): “one who has beautiful eyebrows”.

The mere existence of these terms, of these proverbs—these p̌ap̌upeşi ziťa, underscores what sorts of people the indigenous of the Black Sea coast are. We have been expelled from our ancestral soil with no right to return, and our grief of separation is only further illuminated through adages like—

„Memleketis tis na mogat’u mkvati, ǩurbetis ǩainobaten goişinen.“

“When abroad, you’d remember the stone that hit your head by good means”, meaning when separated from your homeland, you will recall even bad things fondly, because,

„Dobadona şeni na ğuruns, ğura var učarun.“

“Death is not written for those who die for their country.”

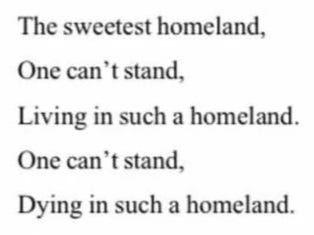

These p̌ap̌upeşi ziťa in particular starkly remind me of a certain slogan:

Solidarity and community is something I have been gleaning more and more value in for a very long time now, and I am eternally grateful for the artists, the poets, and the SWANA activists, creatives, and just folks I have had the pleasure of connecting with. The love and support for justice, creation, and one another among those people is immeasurable. I am forever grateful.

As a [very rhythmic] Lazuri proverb goes:

„Ǩoçi ǩoçi şeni ç̌ami ren.“

“Man is the remedy for man.”

This means exactly what I said: community is healing.

Historically, Lazis have lived in villages—in small, tight-knit communities. I myself grew up in such a village (though not in Pontos/Lazica, but on Old Novgorodian lands of modern-day Russia, as I’ve made mention many a time before). Six people lived there at the time. Only one remains.

And, of course, there are the proverbs of land custodianship.

„Zoğas gyari na gorups mşkironeri var doskidun,“

as they say, for Pontos/Lazica sprawls along the mountainous southern shores of the Black Sea, and “Those who seek their sustenance in the sea shall not go hungry.”

Indigenous peoples know how to take from the land without pillaging. They know the story of the land, how to live harmoniously with it and accept its gifts without robbery. Here, we see a cycle emerge as we return to “Our country has no-one to protect it; pity our black days…”

Indigenous people know how to take from the land without pillaging, but the coloniser does not.

Words of Resistance

As any indigenous SWANA group—any indigenous groups full stop—Lazis write and storytell extensively about resistance, about land sovereignty, about solidarity and grief.

Every indigenous credo is rooted, to some extent, in spiritual and philosophical anarchism.

The Laz concept of ლაზონა (Lazona), literally meaning “Laz field” or “Laz plentifulness” underscores our ancestral connection to our historical Black Sea country.

If you are interested, my flashfiction “Spoils of Famine”, published in The Globe Review, is a retelling of a Pontic folk tale centering solidarity, community care, and mutual aid in the Black Sea Region. It’s less than two pages long. Mild content warning for famine and mention of the Ottomans.

One of my most close-held convictions is my disdain for the rich. I believe in no exceptions when it comes to the atrocious cancer that is the wealthy class, and you’ll be surprised that I actually don’t believe that regarding a lot of things in this world.

„Ar zenginiş oz’ğus oş fuǩaraş oz’ğu umosi ǩai ren.“

“It is better to feed a hundred poor instead of a single rich one,” because:

„Zenginiş kese guyinǯǩet’aşa fuǩaras şuri kyuxteps.“

“The poor would perish by the time the rich brings out their money bag.”

Meaning the rich will, and do, watch the earth burn and every single person perish before they would ever move to soothe the pain of the world. And think about how much they could. Think about all the money the wealthy of the world simply hog without usage. Maybe they’ll donate a tiny fraction, but keep in mind that if you as a working or middle class person, have ever donated money, you have given a higher percentage of your income than the regnant 1% with their donations ever have.

Wealthy “philanthropists” are a joke, they are a lie.

„Çxomi tişen xʒun.“

“A fish starts to rot from the head down.”

Corruption begins at the top. Propaganda trickles down. Every hateful, backward belief exists because someone in power benefits from its existence. Because someone in power requires said belief to remain in power.

All government is terrorism.

But remember:

„Çxoro mtugik ǩat’u doǩires.“

“Nine mice tied up the cat.”

There will always be more of us than there are of them.

And so this all weaves right back into sovereignty, into community and mutual aid, into resistance and radical love for the people—yours and your siblings’ and your neighbours’ and even your enemies’ because the state is the head of the hydra.

None of us are free until all of us are.

An end to all occupation now!

And just to leave you off on a lighter note for once, there’s one Laz proverb I find quite funny and goofy—

„Dido bereşi derdi dido iqven.“

It essentially boils down to “Having many kids brings much trouble.”

I just think that’s real.

~Sfar~Ⓐ🧿֎⨳